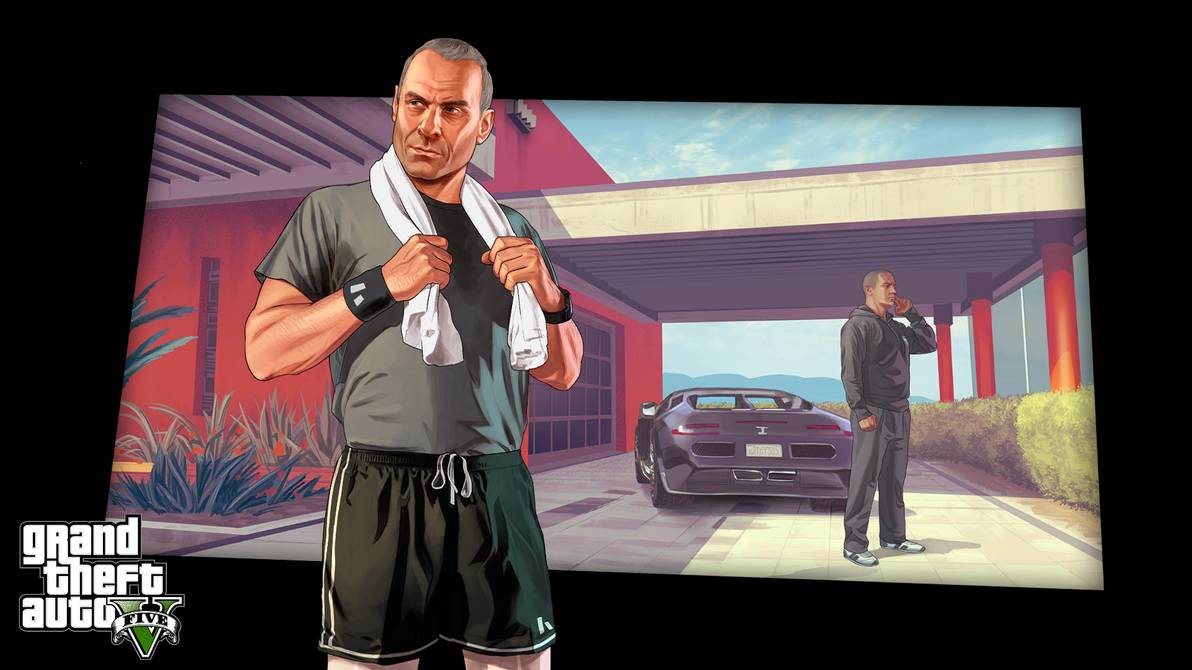

Offshoring is legal in many countries, but is widely regarded as a dirty trick, denying the society that supports you an appropriate share of your earnings - and in a moment of blunt poetic justice, Michael, Franklin and Trevor proceed to “offshore” Weston by rolling the car over a cliff into the Pacific Ocean. It’s typical of Rockstar’s brand of social satire, clownish and macabre and, in this case, spiced with hypocrisy. Six years after the game’s release, the company’s UK businesses stand accused by TaxWatch of moving billions of dollars in profits overseas in order to avoid paying corporation tax, all the while claiming back £47.3 million via a tax relief scheme for creators of “culturally British” art, and doling out large bonuses to UK-based executives. It’s difficult to assess that accusation without knowledge of how development of GTA5 was distributed across Rockstar’s various studios, but well, I’m not sure Michael would be very forgiving. Videogame “satires” of giant corporations have never rung that true for me, largely because some of the most prominent examples are developed by giant corporations. GTA aside, the field is led by Portal 2, a historical and architectural cross-section of a dysfunctional science company created by Valve, the owner of the world’s largest PC game distribution platform. I don’t think it’s impossible to critique the upper echelons of the private sector while working for one of the Powers That Be - if I did, I wouldn’t be writing this for a website owned by a million-dollar events business. But it’s harder to laugh along to jokes about, say, workplace injury or womanising CEOs when they come from those at the summit of an industry that worships crunch and has a lingering sexism problem. Still, credit where it’s due. I enjoyed Portal 2’s caustic, goofy portrayal of a business in which Praying Mantis genes and cut costs alike are visited upon the bodies of hapless boffins. I think Gearbox’s Borderlands has its moments, too, especially when it involves its own design conventions in the satire. The second game sees you tussling with an orbiting arms manufacturer, Hyperion, often while armed with weapons made by Hyperion, and using Hyperion’s widely available New-U cloning stations as spawn points. These charge you a modest pittance whenever you respawn - they make you aware that your time and presence within the game have some kind of dollar-value, precisely in order to show you that, in the eyes of the megacorp, you have barely any value at all. Entwining the satire with how players actually play the game is important - not to evade the dread spectre of ludonarrative dissonance, but because the problem with much corporate satire is that it succumbs to the theatre of corporate excess. Games like GTA and Borderlands see satire largely as a question of wildly exaggerating the ways in which big companies flaunt their power - adboards that eat up the skyline, red carpets and fat cigars, an excitingly imbecilic business vocabulary that obscures or sanitises inequality and cruelty. Their designers teach you to laugh at these manifestations of unchecked wealth, but they seldom see the point of looking beyond them, to rebut the systems of production and distribution that bring them to life. Indeed, all too often they teach you to wallow in them. Devin Weston might get driven off a cliff by the people he’s screwing, but for much of GTA 5’s running time he holds court while other characters look on - lobbing “ironically racist” jibes at Franklin, boasting about his borderline-illegal sexual conquests and, all told, revelling in his own crapulence. Even as Rockstar indulges Weston in cutscenes, so it encourages you to become him, by sponging up property and possessions and playing the stock market, profiting from the chaos wrought by your hits. GTA Online’s longevity is, in fact, premised on the treatment of Los Santos as a mixture of shag pad, piggy bank and shooting range. So where might we turn for a decent example of videogame corporate satire? It’s towards the Rockstar end of the spectrum, but I’m interested to see more of Obsidian’s Outer Worlds. The game casts the player not as a Chosen One but a disposable asset, one of many colonists frozen aboard a drifting starship deemed too expensive to revive. Your rescuer, a Rick Sanchez-esque tearaway on the run from his old employers, only has the means to wake up one colonist, which invests the familiar RPG anxiety about picking the best build for the tasks ahead with unfamiliar callousness: “creating your character”, here, means deciding who to leave behind. The character customisation itself trades the usual line-up of super-duper sci-fi classes for a selection of blue collar jobs, like burger chef and janitor - the professional layer that generally comes off worst from the antics of the people in the boardroom. From the hour or so I’ve played of it, The Outer Worlds is quite creative in extending real-world blights like chronic debt to the detail of its world, though it remains to be seen how much it really deviates from the usual Chosen One tropes, or encourages critical thinking about the world’s iniquities. This is a society in which worker bodies are owned wholesale by the suits, and to kill oneself is thus to lumber your loved ones with a fine for destroying company property. Everybody I’ve met in The Outer Worlds thus far, from ship AIs to repo men, is busy carving out their own niche within the hierarchy and circuitous, Catch-22 logic of Spacer’s Choice, Obsidian’s own spin on Hyperion. One of the first quests you can undertake involves badgering a sickly man to pay the gravedigger upfront for his own burial. At first the boards are easy to clear and your manager is all smiles and praise. Fail to clear lines at a decent pace, however, and that doodle will frown and pester you to make up lost time, deducting a larger and larger wodge from your ending salary. The expectations on you rise as the challenge slowly becomes insurmountable. As each play session goes on, the board fills with mismatches and ineradicable coffee-cup tiles left by gossiping colleagues, till at long last there are no options left and you are summarily fired. It’s at once gentle and succinct and perfectly ghastly - one of the bleakest portrayals of overwork and burnout I’ve come across. I’d like to play a lot more games just like it.