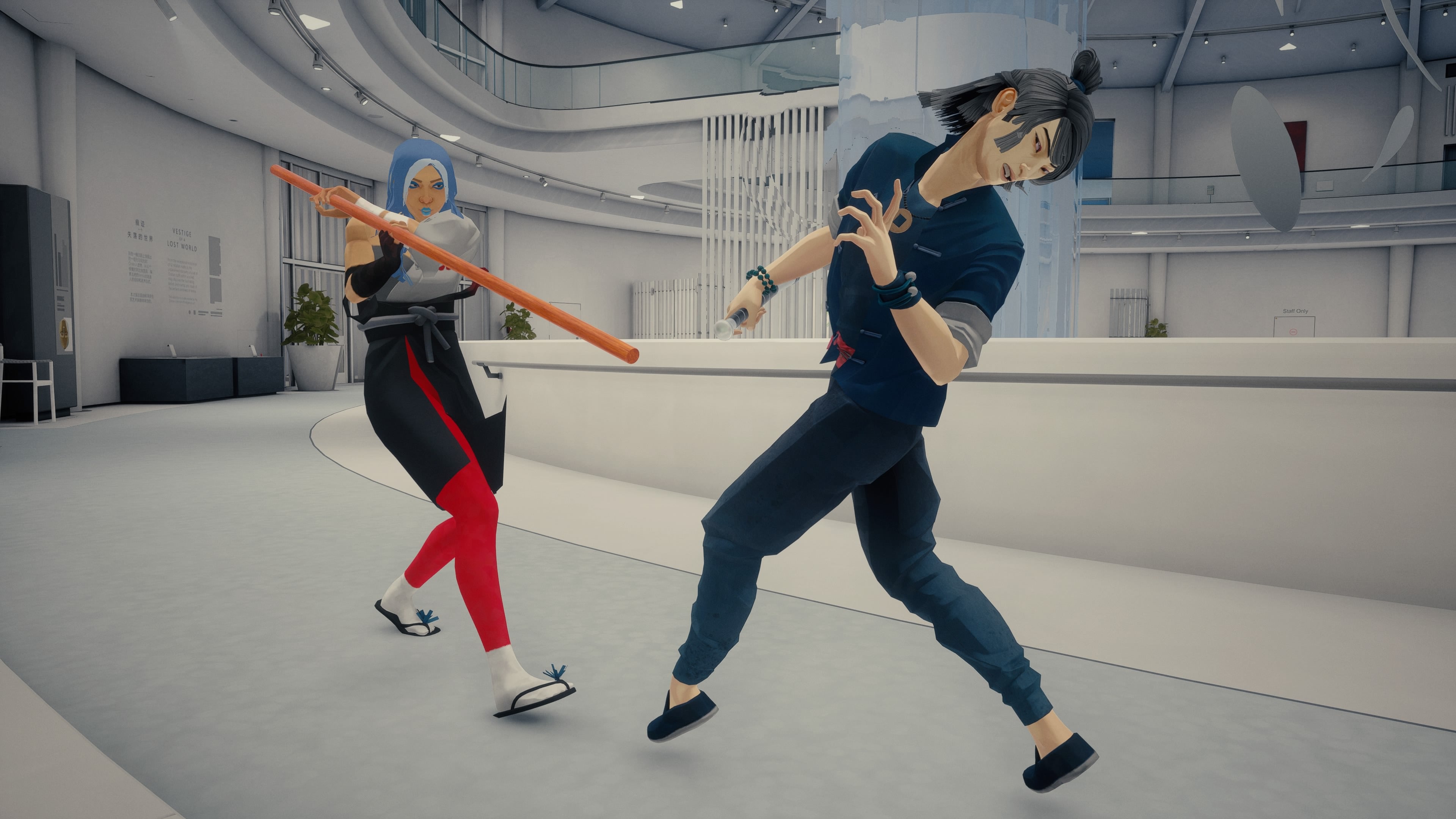

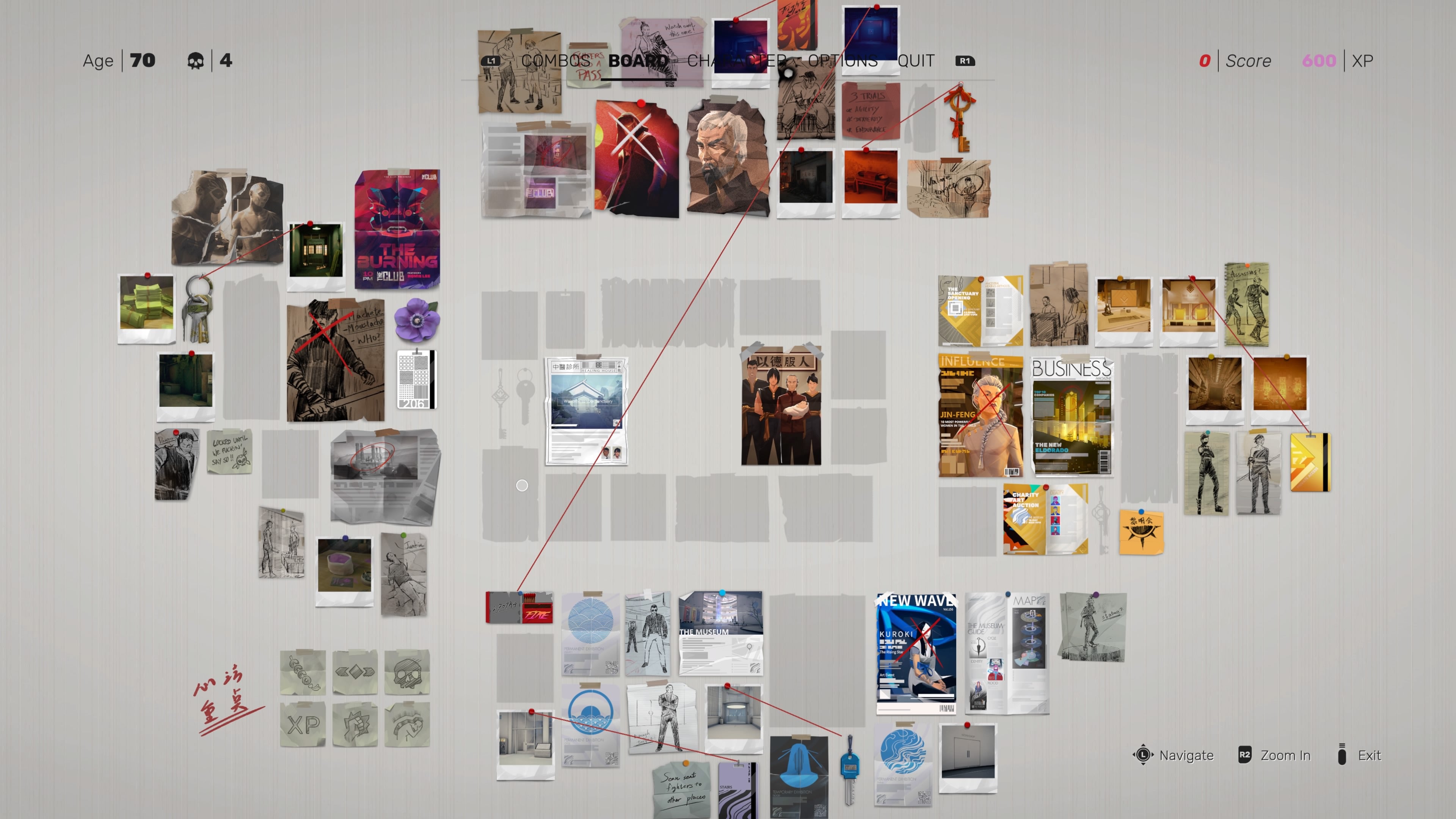

I couldn’t just block her blades with my forearms, and struggled to time her whirling, leisurely strikes. But eventually, I learned to dodge and parry well enough to fit in a few combos of my own - a steadying palm to the solar plexus, then a cathartic shoulder barge and a running ankle-sweep, flooring my willowy adversary and allowing me to land a couple more punches… before helping her gallantly to her feet. Sifu would be a much easier game if the protagonist would just sit on downed foes and clobber them indefinitely, but then again, this is a story about mastering your brutal urges, with every loss of self-control measured in decades. I am more vicious for my rapidly advancing age, but also frailer, my health bar shortening even as the years have somehow polished and strengthened my attacks. Ahead lies the Tower, its dusky golden lobbies and eerie foundations roamed by bodyguards who generally parry your second punch and tackle you for good measure. Somewhere in this building lurks my next target, an equally venerable executive who wields a glowing flail. I am probably too old to survive her hospitality. Sifu’s pendant won’t revive you forever: as you age, its component discs shatter, till all you’re left with is scarlet thread. Take a fall in your seventies and you’ll have to start the level over. You can push on regardless, trying for a perfect run, but the safer approach is to replay previous levels with fewer KOs, stealing back a fistful of hourglass sand from the reaper, while amassing the XP for new moves - the game’s domineering but enjoyable core loop. Among these moves is the ability to snatch throwing knives out of the air, which proves helpful indeed in the second phase of the artist fight. After repeating the first three levels, I walk out of the Museum a trifling 39. Now to bring justice to the occupant of that Tower. Sifu’s ageing mechanic gives its 10 hour+ roguelike campaign a peculiar, mildly dictatorial but very engrossing rhythm of experiment and optimisation. You begin each chapter at the age you finished the previous one. Replaying chapters to shave off years means abandoning any XP or moves unlocked in the current run, but you can unlock an ability several times over to render it permanent. You’ll also discover shortcuts within levels that persist between runs, letting you bypass half the level in some cases, or even take an elevator straight to the final boss. These finds are tracked by a slightly gratuitous detective corkboard back at your father’s old kung fu school or “wuguan”, with threads joining keys to doors, and greyed-out silhouettes for artefacts you’ve yet to discover. Gradually expanded from chapter to chapter, Sifu’s hub space is oddly reminiscent of Hitchcock’s Rear Window, its training floor overlooking the game’s five neighbourhoods, each corresponding to a certain time of day. The environments themselves are spaces immortalised in both films and games: an apartment block’s worth of dealers, a pulsing club with pirouetting clientele, a mountaintop sanctuary that had me thinking wistfully of Hitman. Shortcuts aside, each level is pretty linear, breaking down into a series of room fights, a couple of mini-bosses and infrequent dragon statues where you can activate power-ups and unlock moves. The dense yet graceful composition of these spaces, with gorgeous views peeking over the walls of a tightly framed critical path, recalls Sloclap’s previous fantasy brawler Absolver. I don’t know many developers that can make relatively modest layouts feel this luxurious - distinguished by a trademark interplay of faded metal, posh wood and patterned textiles. I don’t know enough about Pak Mei Kung Fu to assess the credibility of Sifu’s reinvention, but here is how it works in the game: get in fast, open them up with deflections and dodges, shut them down with your palms and elbows. This presented a problem for me at first, because I am a gigantic coward with middling reaction speeds. When I built my own martial arts in Absolver - which, in contrast to Sifu’s fearsome single-mindedness, let you pick-and-choose from scores of moves - I’d always open a combo with a massive spinning kick in the hope of at least forcing a retreat. Pak Mei in Sifu has its share of showstoppers, all brought to life with the bruising finesse you’d expect from a studio made up of martial arts practitioners, but it casts you more often as the flea leaping from body to body, taking people apart with brisk, no-nonsense flurries. You will usually be outnumbered, and most of your named targets have the edge on you at range. Boss number four, especially, can beat you like a carpet while practically standing in a different room. The ace up your sleeve is the Focus bar, filled by dodging attacks (which also adds to your multiplier - Sifu is very much a score attack game). Once it’s full, you can clench a trigger to plunge the world into blissful blue slow-mo and choose special attacks from a wheel. These unblockable techniques are exceptionally helpful against bosses, but they won’t win the game for you, and nor will disposable weapons such as bottles, short swords and brooms. These let you button-mash through most regular enemies until they break; you can also toss them to buy time or interrupt a charge. Just watch out for the enemies who can catch. The game’s guard or Structure mechanic recalls Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice. Punching somebody fills a bar, staggering them when it’s full and creating opportunity for mix-ups, but those bars don’t reset themselves in seconds like they do in Sekiro, so you can take your time chipping away. Adversaries near death can be polished off with a two-button cinematic finisher. Some will get a second wind, shrugging off your takedown and regenerating their health, but these Hulked-out rank-and-file can be a blessing inasmuch as defeating them lops a point off your Death counter, which is how many years you’ll put on when you respawn. Sifu’s representation of ageing is obviously pretty ludicrous - less charitably, you could read it as an excuse to pack several kung fu master caricatures into one playthrough, from arrogant young student through seasoned mentor to wizened legend - but there are some interesting wrinkles (sorry). In the moment, the consequences are few. You don’t have to worry about the evaporating cartilage in your joints, or dimming reflexes; whether 20 or 60, your character darts and pounces as nimbly as ever. But you do have to worry about your diminishing capacity to form synaptic connections. The game’s unlockable moves are bracketed by decade: a warrior in her 60s no longer has space in her head for the rushdown techniques and jaw-rattlers available to her younger self. The changing ratio of health to attack power with seniority is perhaps more intimidating than genuinely impactful, but your increasing strength does occasionally let you brute-force your way through boss fights when you’re close to a restart - placing a welcome dent in the game’s otherwise vertical difficulty curve. Martial applications aside, the spectacle of your hair turning white gives rise to some predictable dread. I always shudder a little when I pass my own age in Sifu: you can feel the reaper’s hand on your shoulder, asking you to pass the controller. Making it all the way through without crossing that boundary is my own personal Platinum. You aren’t required to unlock any moves to complete the game: I sought them out mostly for the joy of seeing them in action. Sifu’s most decisive abilities are your default parries and L1+analog stick dodges - Absolver’s class-specific evasion styles distilled into one. Stuff like the triple-triangle roundhouse kick, or the Street Fighter 4-style hook that absorbs an attack while charging up, is just the cherry on the cake. You can unlock stat boosts at statues, such as a beefier Structure gauge or increased health regain for takedowns, but these level-ups mean little if you’re unwilling to memorise enemy combos and stick your elbow in at the appropriate juncture. Replay is more about amassing Continues and the satisfaction of a smooth run: a sense of growing control and poise that mirrors a dutiful, unobtrusive story about understanding your nemesis and learning to let go of the past, told via short cutscenes and D-pad dialogue exchanges. Sifu offers the promise of reconciliation, albeit at the end of a tunnel full of pipe-waving goons. You will always have to fight, but you don’t necessarily have to kill. Aside from being a rare portrayal of an older person in an action game, Sifu’s accelerated ageing makes me think of time as a product of mental states, and my own experience of “losing time” during periods of severe anxiety. Action games like this can be defined as an exercise in vicariously regaining that lost time through manual skill. They march to a rhythm of expanding and contracting presence, determined by the player’s ability to manage the scrum. This is especially true of games steeped in martial arts cinema, because martial arts films present fighting as kinetic storytelling - the sculpting of a coherent narrative from an obliterating blur of fists and feet. (And also, of a soundtrack: Sifu’s background percussion is expertly tuned to the player-generated audioscape of blocked hits and poise breaks.) As in many action games, some ripostes literally alter the passage of time within the simulation. Counterpunch at exactly the right point in a combo and you’ll paralyse the game with vibrations, as though ringing a bell. To parry and counter effectively is to open windows not just for reprisal but appreciation, expanding your awareness as you store up Focus. To waddle in unscientifically throwing elbows is to collapse the present moment to a juddering circle of panic. This ethic of time manipulation is reflected in levels that obey the same, queasy temporal dynamics as Absolver’s broken world, where crossing boundary stones hastened the sun’s movement through the sky. Here, stepping through a door or dropping down a floor may plunge you into the past, or something that resembles it. Other levels ripple with alternate versions of themselves, their indecisiveness about where and when they are threatening to break your flow in turn. Mastering Pak Mei in Sifu is as much about resynchronising these disordered spaces as it is reorganising faces. This metaphysical uncertainty usefully complicates the game’s representation of China, which I’m not qualified to assess, but which is self-evidently the work of white people for other white people - as underlined by the decision to send out review builds without Chinese voice performances (these are coming in a patch), and by presskits that resemble grab-bags of Orientalist souvenirs. Sifu isn’t really set in China, mind you, but in films set in China, together with Hong Kong, Indonesia, Thailand and Japan. Levels are steeped in reference and homage, to the point of feeling robotic: the bottlegreen street lighting of Sha Po Lang, the already very videogamey hallway fight in Oldboy, the chaotic verticality of The Raid. Sloclap’s blending of these inspirations strikes me as fairly considered, and the game doesn’t, as far as I can tell as a fellow white European, harbour any outright negative stereotypes or slurs. But the art direction freely crosses the line between stylisation and exoticisation, trading in a vision of China that is always richly hued and woven from artisanal materials, even when it comes to the drug dens, and the ability to “blend inspirations” on such a scale is an unavoidable expression of cultural privilege with some straightforward hegemonic overtones. It implies that East Asia at large is just a mood board for overseas creators and connoisseurs with more resources, status and connections. The setting’s most important parallels in film aren’t Chinese movies, but the placeless, global underworlds of John Wick and Kill Bill - cinematic universes dreamt up primarily by white Westerners, mixing together cues from South Korean and Japanese film-makers. Ruminations on the nature of time aside, the value of the game’s temporal fluctuations is that they introduce a measure of critical distance, inviting you to think about levels as projections and aberrations, rather than authentic and trustworthy recreations of other cultures and their landscapes. This is especially the case in the Museum level, where the artistic choices are literally on display, with exhibitions forming a journey through your adversary’s Japanese heritage, side-by-side with riffs on European and North American artists like Andy Warhol and Damien Hirst. These misgivings about its representational politics notwithstanding, Sifu is a brilliant, eccentric fighting game. It expects close attention and patience, and rewards you with scuffles of incredible intensity. Its campaign structure is bizarre but engaging, coaxing you to replay levels not just for additional moves or to shed a few decades, but to enjoy what you’ve painstakingly committed to muscle memory. It could take itself a bit less seriously. Certain terrain kills and crowd control sequences recall Jackie Chan’s action comedies and sillier beat ’em ups from the PS2 era, but Sloclap never delivers on this comic potential. The story is ponderous and mechanical, more suffocated than energised by the familiar theme of hatred consuming the hater. A less reverent approach might also have helped the game untangle its own Orientalist worldview and perceive itself not as a solemn curator of East Asian culture but an appreciative tourist, galloping around with a camera. Where Sifu most earns its seriousness, for me, is in that largely unspoken marriage of combos and counters with questions of perception and synchronicity. This is a game about the punch-drunk unevenness of time, and the way that unevenness depends on the mind you bring to bear.