Despite being considered the most important composer in the impressionist movement, Claude Debussy was not fond of the label. “I am trying to do something different, an effect of reality… what the imbeciles call impressionism,” Debussy wrote in 1908.“A term which is as poorly used as possible, particularly by the critics, since they do not hesitate to apply it to [J.M.W.] Turner, the finest creator of mysterious effects in all the world of art.”

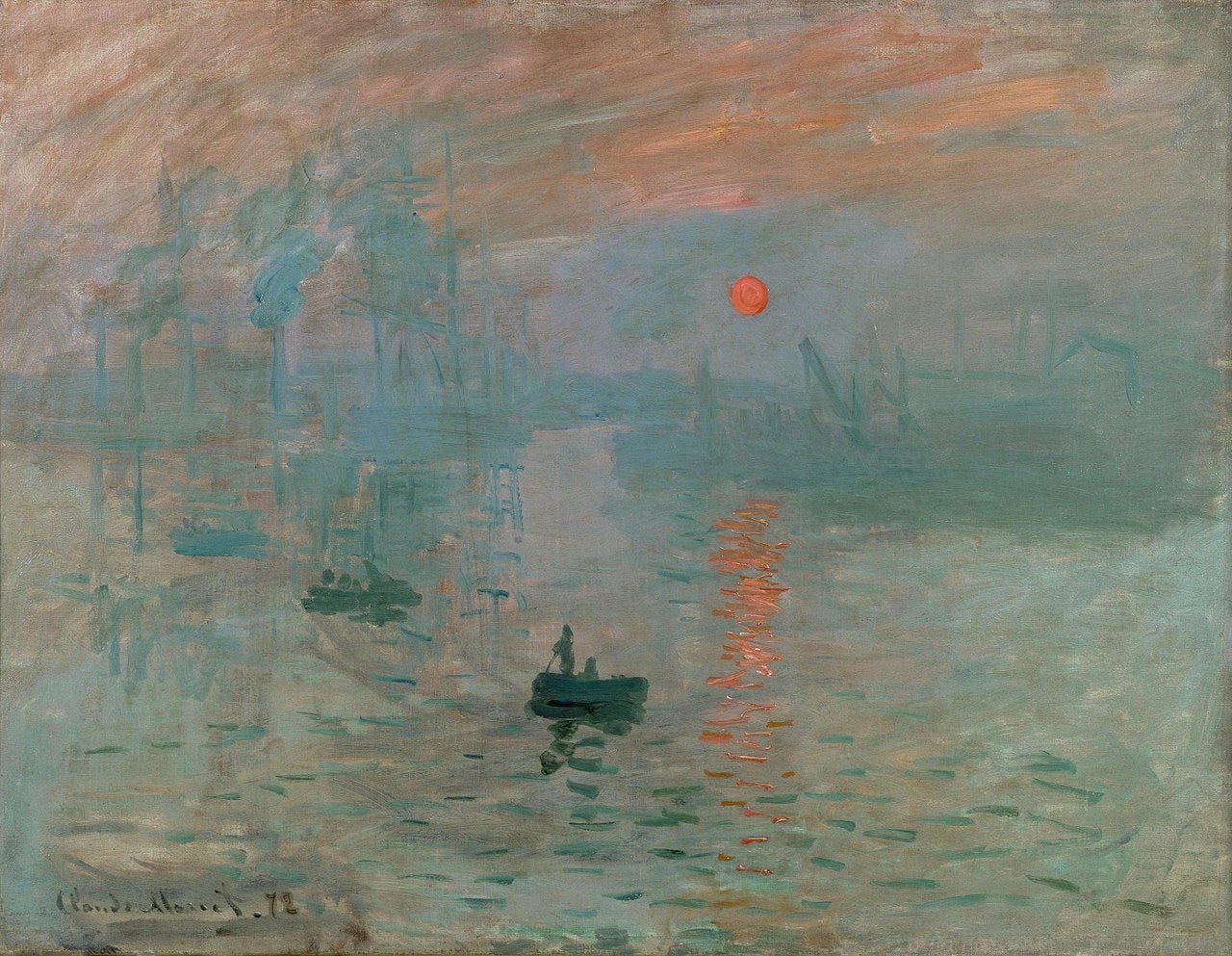

Debussy was probably wary of the term due to its dubious art world origins: coined by critic Louis Leroy, it was initially used in a derogatory manner to review an exhibition by painters including Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. “Impressionism” was used to ridicule the painters’ loose brush-strokes and casual composition, which Leroy (and many others at the time) considered unfinished. The term was then applied to Debussy’s music, with critics finding similarities between the painters’ use of contrasting colours, light and blurred backgrounds, and Debussy’s use of orchestral colour and harmony to make listeners focus on an overall “impression”.

Of course, many of the artists Leroy criticised chose to embrace the impressionist label, and now it’s also used to describe the work of 19th-20th century composers such as Claude Debussy, Maurice Ravel, Paul Dukas and Erik Satie. And although Debussy and Ravel disliked how the term was applied to their music, I’d like to suggest the ideas behind impressionist music can be usefully applied to yet another art form: video games, of course.

The first game that got me thinking about this was Spiritfarer, which explores the theme of death by asking the player to care for animal friends and ferry their souls to the afterlife. It’s a heavy topic, but the game creates a soothing atmosphere with its music, vivid art and homely tasks. It’s a game focused on mood creation, without a detail-heavy narrative or extremely complicated game systems.

To me this all feels very familiar to some of the key ideas behind impressionism, namely, a focus on evoking feeling, and layering individual colours to create mood. Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune, considered one of the most important pieces of impressionist music, was described by Debussy not as a direct synthesis of Stéphane Mallarmé’s poem but as “a succession of scenes through which pass the desires and dreams of the faun in the heat of the afternoon”. As Dukas put it, impressionists were interested in using chord progressions to create a “series of sensations rather than the deductions of a musical thought”. It’s about the reaction to a subject, rather than depicting the subject itself: the feelings of the faun while dreaming, instead of the actual dreams of the faun.

So Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune doesn’t have a clear structure in the traditional sense: musical motifs are instead passed between members of the orchestra, with solo lines used to highlight an instrument’s timbre (its distinctive sound). Each appearance of the main theme is treated differently, with varying textures and colourful harmonies, allowing it to be heard through a different lens with each repetition. The rhythm feels fluid thanks to the shifting 6/8 and 9/8 metres, while the chromatic melody outlining a tritone (known as the “devil’s interval”) makes the tonality seem hazy. All of which gives the piece an unsettled feeling, somewhere in-between waking and dreaming.

Similarly, many aspects of Spiritfarer’s afterlife world are left deliberately vague - it’s a place outside time. The game discusses death without directly depicting it, exploring the emotions surrounding death through relationships with brightly-coloured animals, and farewells said at a mystical bridge. It’s split into multiple stories, with quests given by a range of unique characters, but key themes (like compassion and saying goodbye) are repeated throughout.

Back in 2019, creative director Nicolas Guerin told me that developer Thunder Lotus wanted to focus on legacy and transition in Spiritfarer. “You look at the legacy of all the generations before you, and you are there because of all the interactions that shaped you as a human being,” he said of the themes. In other words, viewing yourself as the sum of loved ones who came before you. So like impressionist music, Spiritfarer layers individual colours, emotions and moments to impart this message, and create mood. And mood is the most important aspect of Spiritfarer: encouraging a positive attitude towards death, something developer Thunder Lotus said was the key idea behind the game.

Another game that shares similarities with impressionist music is Gris, a platformer by Nomada Studio. Gris has an even hazier approach to narrative than Spiritfarer, with absolutely no dialogue, minimalist instructions on how to use game mechanics, and progress largely shown through the return of colours (and accompanying abilities). Gris really aligns with Debussy’s description of form as a “succession of scenes” - it’s structured as a series of moments, often bringing the player to caverns of no practical function other than to widen the camera and encourage the player to admire the view. It’s focused on creating sensations: a feeling of physical heaviness is conveyed at the start when the player’s movement is limited to trudging, but later sequences convey falling or flight. Even its smaller details are designed to elicit an emotional response - jumping on a mushroom to make it tinkle and ripple creates a lovely moment of fragility.

Along with being beautiful in their own right, these moments combine to evoke specific emotions in the player - sorrow and melancholy, then perseverance. It’s an exploration of the stages of grief, all without directly depicting loss, or uttering a single word. And apparently I’m not alone in feeling this: when reviewing the game Vikki Blake described Gris as “snatches of sentiment coming in dreamy, ethereal wisps, a warm, gloopy mess of incomplete sensations and emotions”. Something that could just as easily be applied to a piece like Ravel’s Sonatine; the first movement of which makes use of shimmering tremolo rhythms, harmonic parallelism, and slight syncopation to create a shifting, floating sensation. Fleeting moments, indeed.

These are just a couple of games that seem to lend themselves to comparisons with impressionist works, but perhaps some of the ideas behind impressionism can be found even within large open-world titles. Assassin’s Creed Valhalla establishes a sense of its world through appropriately-named “World Events”: short and often unresolved snippets of life that build up a wider picture of Ubisoft’s Anglo Saxon England. The ones that evoked strong emotional reactions (fear when trapped in a witch’s poison hut, sorrow at meeting an elderly farmer with dementia, and a moment of serenity shared with a couple admiring the view) remain my strongest memories of the game. Combined, they built an atmosphere in the game that I struggle to put into words - but I can recall the feeling quite clearly.

Perhaps it can be said that games are particularly adept at handling themes and moments, and are possibly better at this than rigid storylines. Beyond visuals and sound, we build up a picture of a game world through hundreds of interactions, from individual inputs to finding the limits of the rules through experimentation. Unlike cinema and literature, it’s often hard to keep a player pinned into a narrow and focused authorial vision in video games: an alternative approach is to let them uncover many themes and colours within a game space, and piece them all together. Viewing games through the window of impressionist music highlights these strengths - and when games lean into this focus on mood and atmosphere, they can unlock something quite powerful.