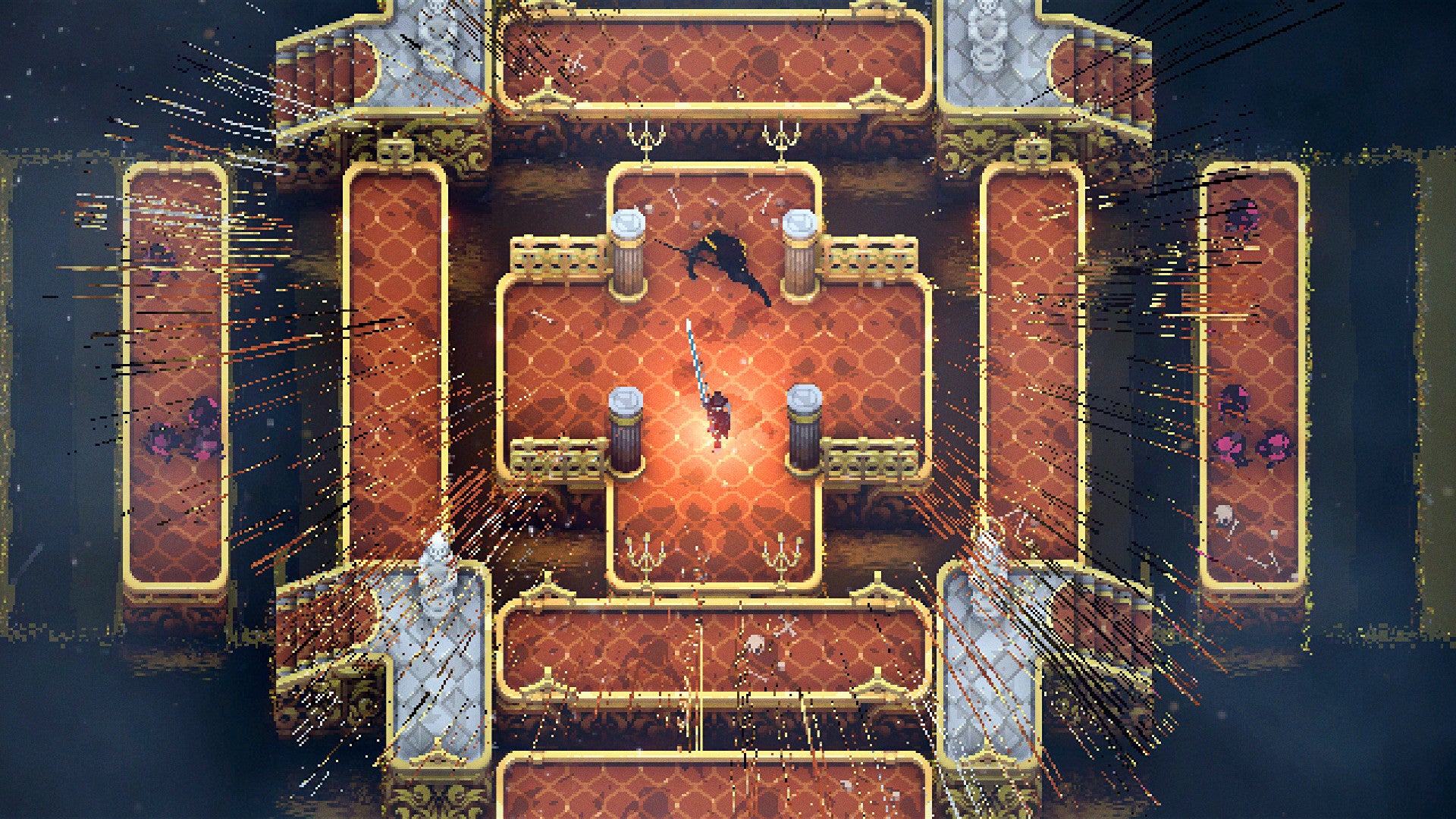

I watched a brilliant documentary on Chang’s apartment last night. And by the end of it I thought: cor, maybe we’re all thinking about this home stuff wrong? Maybe Chang’s etch-a-sketch lifestyle is the way to do it. Focus on what you love and conjure the idea of rooms around that and that alone. Opt for a house that slides into place only when you want it to be there. Harmoniously - a suspicious kind of harmony really - I then spent today playing Loot River. Loot River is an inventive and deeply satisfying roguelite, a top-down affair with a touch of Souls to it. There are a lot of these. But Loot River has a big idea, and it’s an idea Chang might approve of. The game plays out on dungeons made of floating tiles - tetrominos put you in the right headspace, but there are lots more shapes - and as you move around with the left stick, you can move the tile you’re on with the right, sliding it through the water from one spot to another. All of this while hacking and slashing (soulslike combat with parries and heavy swings and a button-stab lock-on) and finding treasure and leveling up and getting better weapons and armor and then dying and losing it all and starting over. It’s fantastic. It turns out that being able to move the floor around brings a lot to a game about hacking and slashing. When you can move the part of your surroundings that you’re currently stood on, you pay a lot of attention to what else is around you - and that fits neatly with the hyper-vigilance that roguelites require. This is a genre that’s often about deciding when to engage and when not to engage. So while there are lots of neat movement puzzles with the tiles, as you shift floorplans around to clear a blockage, or find the right shaped piece to allow you to enter a new part of the map, most of the time when I play I’m moving tiles and thinking about combat. It’s like a roguelike where you ride around on a Routemaster, really. Say I’m safe on my tile and there’s another tile nearby with eight baddies on it. Maybe I rush up, allow a few baddies on, and then dash off again, separating myself from the main throng to do them in. Maybe I connect and reconnect and disconnect tiles like circuitry, maintaining the flow, turning things into a sort of factory plan of destruction, with me chewing through enemies at a rate that suits me. Routemasters! Circuitry! So many competing analogies, but that’s no surprise I guess, in a game that manages to chuck familiar things - roguelikes! Tetrominoes! - together in a fresh way. Chuck in a range of enemies rendered truly hideous by the gritty, sherberty pixelart. Lobbers! Runners-and-eaters! Sword people of all stripes! Poison bombs! Horrible bosses! They’d be fun to take on in any game, I think, but in a game where you can zip up on a handy piece of flooring, and then dash away again, you get truly delirious options. When to engage? How to approach? Which angle to approach from in the first place? Throw in magic and different weapons and artefacts that allow you to modify the game in certain ways and you have something special. The magic and weapons, incidentally, provide the progress system, which in this particular roguelite is the litest of lite touches. Level up, score cash, attribute-boosting loot and maybe a few killer specials, like a feather (I love this one) that allows you to appear on the other side of your foe after you’ve landed the first strike. Die and that’s all gone. You can’t take any of it with you. What you can take with you - kind of - is any weapons or spells that you’ve unlocked by earning a currency called Knowledge, and then getting back to the main hub between levels to cash it at the shops. But even this isn’t that simple, because you use Knowledge to unlock weapons and spells, but the game then scrambles them into your hands at the start of a new run with no choice or influence from you. You pay Knowledge to make the pool of potential approaches broader, but that’s it. And also, of course, you lose any Knowledge you haven’t cashed in when you die. It’s maddening. And all said it’s brilliant, I think: brutally mean but also ingenious and characterful. I love the fact that I spend a lot of time adrift on the river, standing on my little safe tetromino, wondering whether to bring it up against the next spar of land I can see, where eight horrors await me. I love that simple twists, like an enemy who locks tiles together until they’re dispatched, or a fire trap that spreads, or a tile of a different height that requires stairs to access, make everything fresh again. I love a whole screen of accessibility options, including font size, platform guides and enemy outlines, as well as screen shake, a colour-blind mode, tweaks to vibrations and UI and an easy mode that reduces enemy HP. I love a mysterious world built around a hub that is filled with statues of body parts and grass littered with bones. I love the oily sheen on the water that the game’s tiles scud across: lazy ripples, light shattered into fuzzy dots, the lap and splash of a wretched tide. I love the funereal drone of the music. You know that moment in a good roguelite where you’ve overextended yourself, but you’ve also won riches that you don’t want to lose before you can bank them? This is what Loot River is built for, ultimately: I race around the world, dashing from one tile to another, breaking off from a little continent, an archipelago of burning wood and then searching, searching for the level’s exit as I eye my tiny health gauge with fear. A procedural dungeon-crawler where you can rescramble the once-scrambled levels? Gary Chang would be proud.