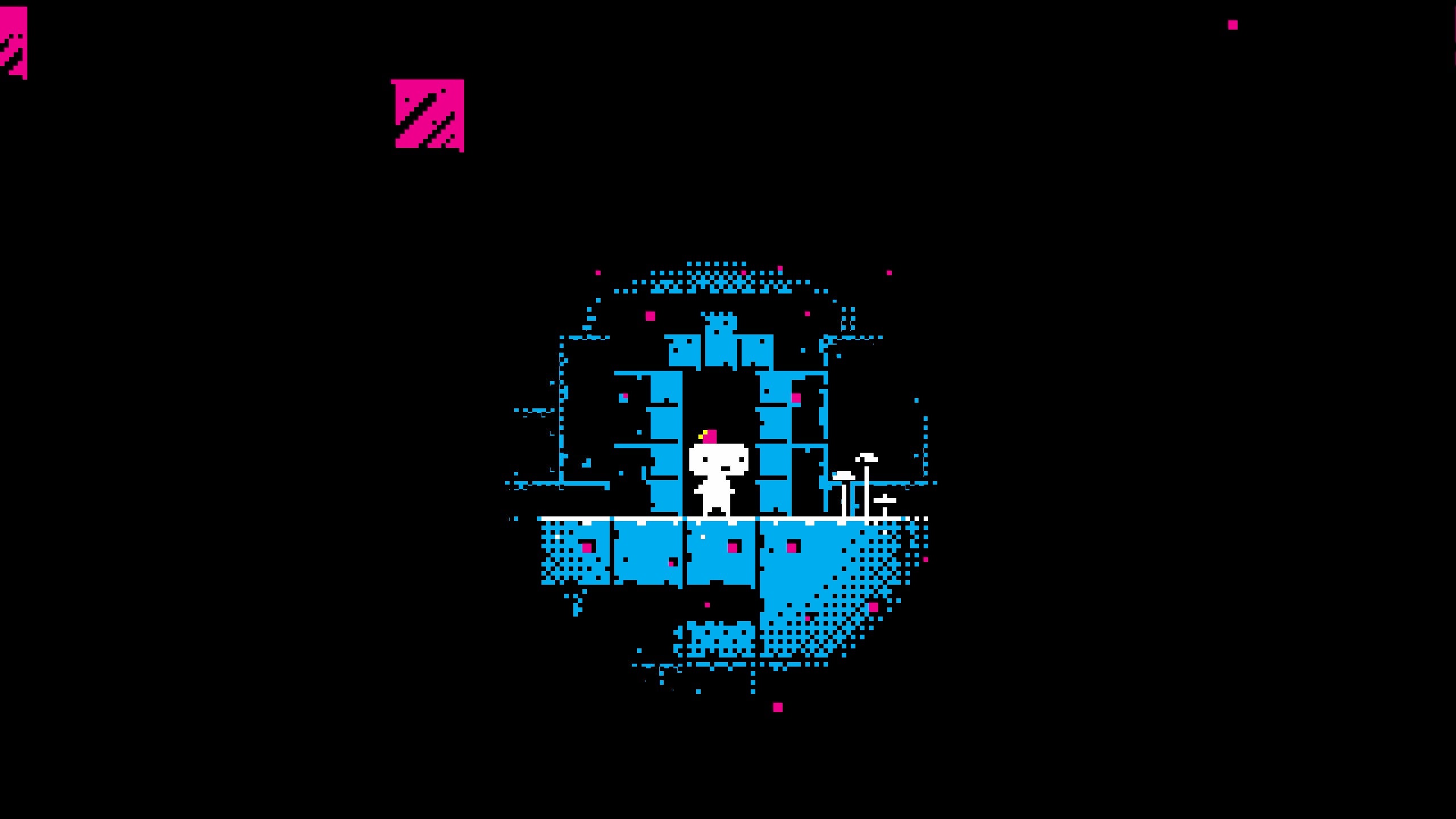

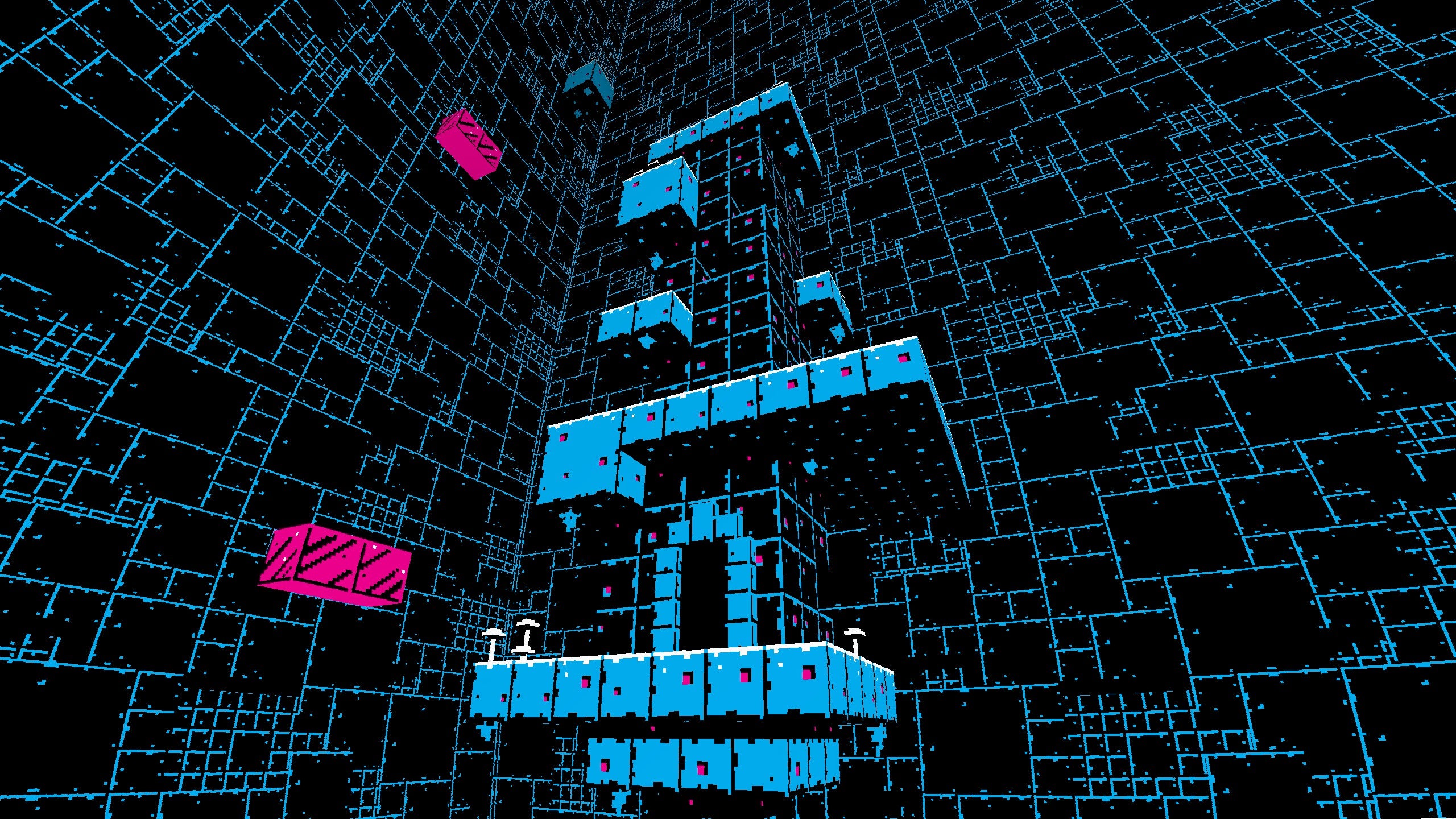

But it’s been 10 years since it was released, which is a long time, and somehow within all of that, I had never played it. Until now, that is, and it’s an interesting place to look back on the game from. There’s no noise surrounding it now, no drama. All that hullabaloo, it’s gone. Now, really, there is only the game. And what a game. I’m not here to give you a controversial hot-take on how time has ravaged Fez and revealed it to be rubbish, because it hasn’t. In fact, I’m partly here to tell you the opposite and how time doesn’t seem to have touched Fez at all. It’s remarkable how fresh it still feels. It could have been released this year. Those blue skies and Mario grass-greens are still dreamily nostalgic. Those pixel edges are still crisp. Those dinky cube worlds still appear delicate enough to belong in a gallery somewhere. Fez still turns heads. And the “gimmick”, as Oli once called it, that central mechanic of a rotating 2D world - which is actually a 3D world viewed side-on that you can spin around - which reveals secrets and rearranges platforms so you can get to places you previously couldn’t: that is still brilliant, still endlessly brilliant. Dozens of hours in, I still marvel at how levels realign themselves. And for this to feel so new even after other games like Monument Valley have normalised it - it’s testament to the way it’s implemented here. But these are surface level things, really. You understand and enjoy these things when you begin, and for a long time, Fez doesn’t necessarily seem like anything more, which would be absolutely fine - it would still be a lovely game. But gradually, you see hints of something else: markings you can’t understand or suggestions of secrets you can’t quite get to, and your brain can’t quite bridge the gap to find the solution. So it begins to bother you - not hold you up, just bother you. Then came the notebook, and I wondered when this would happen because I distinctly remember the pictures of other people’s Fez notebooks from the time, waved like trophies proving they’d solved the game’s deeper mysteries. You know, for a while I thought I wouldn’t need one, that I could finish the game without one, because I was so close to 100 per cent completion it seemed silly to use one now. I was a fool. 100 per cent is where Fez really begins. It’s almost as if by ending once, Fez frees itself of having to entertain everyone and is able to focus on challenging people instead. And it’s the areas you left for later, that you couldn’t solve before, that come back into view, and with them comes a change of pace. The breezy progress stops and a harder-earned progression settles in. I spent hours thinking about that giant bell. I must have returned to it a dozen times in the hope of shaking something loose or understanding something more. I’d encountered it early on and seen the markings on the side, and made a note of them, noting anything similar I encountered along the way. But no solution had appeared. The bell still stood as it once did, teasingly enigmatic. I thought about it so much I even once believed it controlled the water levels and would reveal drowned lands when rang. I spent just as long peering through the telescope, looking at those tetromino shapes in the sky. Again, I could sense a puzzle around me - and the game’s map reminded me one was here to solve - but I could neither work out what it was nor how to get at it. Fez does that a lot, teases you. It places things you don’t understand around you, challenging you to try and figure them out. Take those posts with the line of symbols on them. I’d originally expected the game to simply give me an item that would open them up. Another game would, I’m sure, but Fez doesn’t. So it is that you seem at a dead end and to be going around in circles, when something clicks and a jolt of excitement shoots through you as you race to an area to test a theory that just materialised. You could have been turning this problem over in your head for days. You try it, you hope, and you hold your breath as something different happens. You’ve done it! The feeling is as relieving as the puzzle was frustrating. And another layer of Fez peels away. This process can take some time, and can begin to feel laborious as you traipse back across levels to try things out, regardless of the secret doors and portals put there to help. But there’s something I greatly admire in it, both in how a game can be audacious enough to suddenly require a lot more effort from you, and in how, by repeating itself and not conjuring new places for you to go, it allows time for you to go back and appreciate what’s around you. So many other games are a blur of progress such that you’re only left with a hazy idea of what happened at the end. But Fez slows down, lets you breathe, lets you just be there, free to see the details you missed the first time around. There’s a wonderful moment after you first finish the game where you’re given glasses that let you see the world anew, in first-person 3D. It’s ostensibly done so you can solve some harder puzzles, but really I think it’s a way to have you admire all of the work, from yet another angle, all over again. And Fez is a world of work. It’s a world of painstaking detail. Everything is hand-placed and bespoke. There’s no sense of chance here. Every rotation of the world has been thought about, every realignment considered. And as you begin to touch upon the harder puzzles linked to the story of the world and the society living there, and their language and codes, the depth of thinking behind Fez almost bewilders. It’s when you start to see all of this you can’t help thinking about the mind that made it, the person whose presence you cannot help but feel in such a personal project of a game. To me, creator and game are inseparable here. And that person is, of course, Phil Fish. But to think of Fish is to think of the drama that surrounded him and ultimately led to his abrupt departure from games and the cancellation of Fez 2. It’s to think of Indie Game: The Movie and the emotion you can see bubbling within him every time he’s on camera, where he talks of the turbulence he experienced making the game. I don’t think it’s a stretch to say that making Fez nearly broke him. And it’s in thinking about all of that that the celebration of Fez, 10 years later, falters. How can we celebrate something which ultimately led to that - to such a talent leaving the games industry for, apparently, ever? I wonder where Phil Fish is now and what he’s doing. I hope his life is calmer. There have been rare sightings but nothing decisive, nothing that can pin him down. I wonder how much attention he pays to games now - it’s not as though a lifelong passion such as his (he says in Indie Game: The Movie that he knew from as young as four years old that he wanted to make games) can be easily turned off. I wonder whether he realises it’s Fez’s 10th anniversary at all. But then how can he not? You do not spend five difficult years making a game only to forget when it came out. I wonder whether he thinks about making games again one day. Perhaps he does, perhaps he shows them to one or two people but no one else. But without others to gauge his success by, what would fuel his fire? Maybe he has attempted Fez 2, only showed it to no one. But I doubt it, and for various reasons, I hope he never does. Fez doesn’t need a sequel - it never did. Nothing could ever be as vibrantly fresh and surprising a second time around. Moreover, nothing could ever be as painstakingly detailed or excessively generous and complete, because to pursue such an end would be to break oneself all over again, and only with naivety is such a thing usually accomplished first time around - and at great cost. And that is Fez, brilliant but damaged, singular and unrepeatable. A cause for celebration but also for continued concern. A mandatory mention when you talk about indie games. What would Phil Fish say about it? Well, I thought I’d ask him, not that I ever thought he’d answer. Yet to my surprise, he did, and I’ll publish my interview with him tomorrow.

.jpg/BROK/resize/690%3E/format/jpg/quality/75/fez_bell-(2).jpg)